Online discussions can help you prepare for class, learn discussion skills, practice your writing skills, and learn from others. To be successful, you need to translate your face-to-face discussion skills to the online environment. Remember that online discussions are first and foremost dialogues, not writing assignments. The following tips highlight key features of effective online discussion strategies, whether for discussion groups. These are general strategies. Be sure to read and follow your course-specific discussion assignment instructions.

Writing a post

Review the discussion instructions.

Your discussion may be more open-ended or there may be specific discussion prompts. In the case when there are specific discussion prompts, read them carefully and respond to all aspects of the prompt. Also, note whether your instructor wants you to include references and, if so, how many.

For more open-ended discussions, complete any of the assigned readings prior to drafting your post. You may be asked to think of a thesis and how to support it. Then read the other postings and see how they support or contradict your idea and write about this. Another strategy is to look for postings that lack evidence and probe for some. You can also turn your thoughts into questions or share alternate viewpoints. Remember, though, that opinions aren’t arguments. Be sure to support what you say with references to course materials or outside sources, such as readings.

Use keywords in your title.

Online discussions can generate many messages, so you need to consider efficient ways to make your contributions. To help the other participants quickly understand what your post is about, be sure that your title clearly indicates the content that will follow. “My ideas about today’s readings” isn’t nearly as clear as “My opinion on Freud’s theory of mourning and melancholia.” Your title could even summarize the opinion, argument, or question that you raise, like in the following: “Freud’s theory of mourning and melancholia: A false divide.”

Encourage discussion.

If you’re the first to post, strive to encourage discussion. Get others thinking (and writing) by making bold statements or including open-ended questions in your message. Those who post first are most often responded to and cited by others. Remember to check back and see if and how others have responded to your ideas.

Make posts short, clear, and purposeful.

Review the discussion guidelines for how long your posts should be. If length is not specified, write one to two meaningful paragraphs because long messages are difficult to read online. Another consideration is to make only one main point in each post, supported by evidence and/or an example. Be concise (Vonderwell, 2003).

Your stance need not be forever.

It can be intimidating to take a stand on an issue at times, especially when you put it in writing, which we associate with permanence. Remember that you are allowed to change your mind! Simply indicate that with the new information raised in the discussion, you have changed your stance. Learning is about change.

Other practical considerations for discussion board postings

It can be frustrating to read through a busy discussion forum with lots of posts and replies. Make sure to create new threads if new topics evolve in the discussion. Subscribing to receive email alerts of new postings can help participants keep up with a conversation without checking back into the discussion forum repeatedly. You can configure the tool to receive alerts whenever a new post appears, or receive a daily summary of the posts.

Responding to other posts

Make the context clear.

Make the context clear.

An informative title will help, but also consider including in your reply a quotation from the original message that you’re responding to. If the original message is lengthy, cut out what is not relevant to your response. If the original has many paragraphs, you could place your comments in bold between the paragraphs to give readers the context for your ideas (Vonderwell, 2003).

Add value to the conversation.

Saying “I agree” does not move the discussion forward. Ask yourself why you agree and explain your rationale so that others have something else to respond to (Vonderwell, 2003).

Ask probing questions.

Consider using the following questions when trying to extend a discussion:

- What reasons do you have for saying that?

- Why do you agree (or disagree) on that point?

- How are you defining the term that you just used?

- What do you mean by that expression?

- Could you clarify that remark?

- What follows from what you just said?

- What alternatives are there to such a formulation? (Roper, 2007)

Feel free to disagree with your classmates.

To air different perspectives or help others clarify their thinking, you may need to contradict a classmate. Remember to disagree respectfully (no name-calling or obscenities) and support your point with evidence. Do not feel bad about offering a different interpretation. Your contribution should help to make the discussion more productive for all involved.

Work to create group cohesion.

Discussions are about group learning. When you function well as a group, you will be more open to all the benefits that this type of learning can offer. Give positive feedback to one another, use light humour, avoid comments that could be taken as insulting, use first names, respond promptly to each other, and offer assistance. Also remember the lack of nonverbal and vocal cues in the online environment. You’ll need to label emotions (e.g., “I’m confused about this” or “I feel strongly”) because no one will pick up on how you feel otherwise.

Be aware when postings prompt strong emotional responses.

If you feel very emotional about a message, wait before responding. It’s very easy to write something in the heat of the moment and then wish you could retract it. If you send it to the discussion, the damage is done. Even waiting overnight can give you enough distance to respond in a calmer and more professional manner.

Developing a positive perspective

Engage in online chats.

Engage in online chats.

Online chats can provide an opportunity to ask questions or make comments during an online lecture. Try to make your comments concise and clear. Remember to be respectful and professional: don't write anything that you wouldn't speak in class. Also, avoid clogging up the chat with links to extraneous resources. Stay focused and aim to add value to the class experience.

Be open to new ideas

Discussion is about hearing what others have to say and working to shape and re-shape your own thoughts and perspectives. Different perspectives can further everyone’s understanding of the issue or concept being discussed—they represent opportunities for learning.

The online environment comes with many benefits, including learning from your peers in addition to your instructor. Use the time productively to hone lifelong skills and refine your ideas about the course content.

References

- Roper, A. (2007). How Students Develop Online Learning Skills. Educause Quarterly, 1, 62-65.

- Vonderwell, S. (2003). An examiniation of asynchronous communication experience and perspectives of students in an online course: A case study. The Internet and Higher Education, 6(1), 77-90.

- Yu, L. et al. (2016). When students want to stand out: Discourse moves in online classroom discussion that reflect students’ needs for distinctiveness. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 1-11.

The following book provides foundational principles, inspirational examples, and many resources to guide our work as we design, develop, and facilitate an engaging asynchronous online discussion prompt.

The following book provides foundational principles, inspirational examples, and many resources to guide our work as we design, develop, and facilitate an engaging asynchronous online discussion prompt. There are many

benefits to having classroom discussions, whether they are online or in person. Whatever the format, discussions allow learners to

expand their learning outside the classroom through interactive dialogue

with their peers and the instructor.

There are many

benefits to having classroom discussions, whether they are online or in person. Whatever the format, discussions allow learners to

expand their learning outside the classroom through interactive dialogue

with their peers and the instructor.

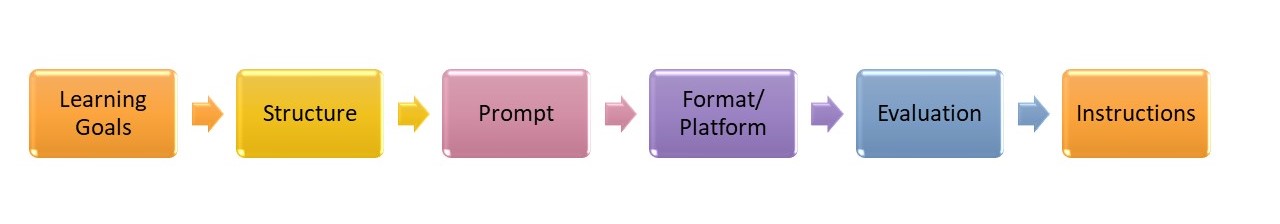

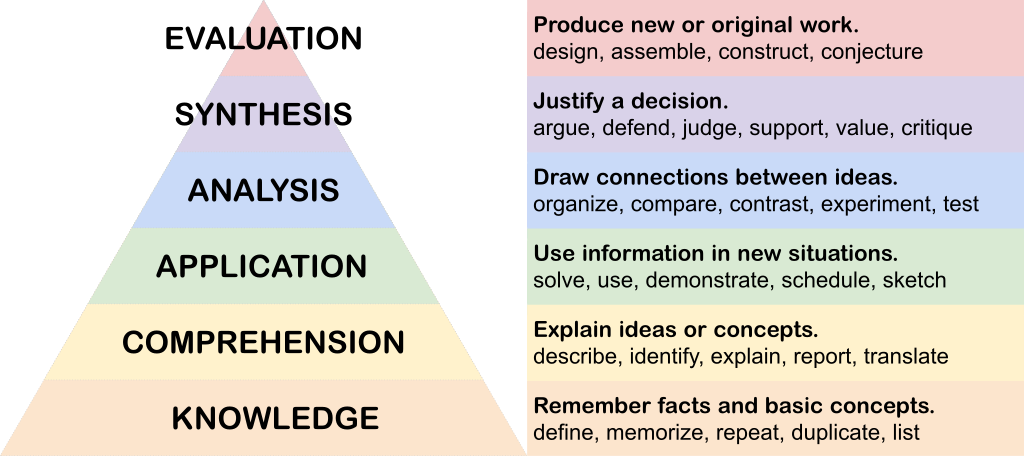

Once you have determined that a discussion is the

appropriate activity to meet the learning goal, consider the task that you wish

learners to engage in. In this book, we call it the structure of the discussion.

Choosing a structure will depend on the learning goal. For example, if the

learning goal involves students understanding the perspective of various stakeholders

in a scenario, a Role-Play may be a good way to go. If the learning

objective is for students to recognize a concept in different settings and/or

to learn from examples (i.e., inductive learning), then Picture This Example

is a good choice. If the learning outcome is focused on assembling a toolkit or

preparing for professional life, then Crowd-Sourced Research is a good

structure.

Once you have determined that a discussion is the

appropriate activity to meet the learning goal, consider the task that you wish

learners to engage in. In this book, we call it the structure of the discussion.

Choosing a structure will depend on the learning goal. For example, if the

learning goal involves students understanding the perspective of various stakeholders

in a scenario, a Role-Play may be a good way to go. If the learning

objective is for students to recognize a concept in different settings and/or

to learn from examples (i.e., inductive learning), then Picture This Example

is a good choice. If the learning outcome is focused on assembling a toolkit or

preparing for professional life, then Crowd-Sourced Research is a good

structure.  Discussions can be evaluated in many different ways. It can

be done automatically, where learners get full make if they engage in a set number

of posts and replies. Some educators use more elaborate schemes that give users

choice, for example, they must engage in 3 of the course’s 5 discussion, and

during these posts they must make 2 significant contributions that advance the discussion

and must make 4 small posts that simply encourage the discussion (e.g., giving

kudos to their peers).

Discussions can be evaluated in many different ways. It can

be done automatically, where learners get full make if they engage in a set number

of posts and replies. Some educators use more elaborate schemes that give users

choice, for example, they must engage in 3 of the course’s 5 discussion, and

during these posts they must make 2 significant contributions that advance the discussion

and must make 4 small posts that simply encourage the discussion (e.g., giving

kudos to their peers). Role-play: The instructor assigns roles or characters to learners and then gives

them scenarios to act out in the AOD. Note that

these are great alternative assessment methods and help to really learn

how much learners know about a given topic. An important tactic to

keep in mind is to

survey learners prior to assigning roles and to purposely put each learner into a role that is new or different than the learner's own

personal views or values. For example, make a learner with conservative political views play the

role of a person with liberal political views,

or young person play the role of an elderly resident. This way the

participants are forced to learn about new views and opposite viewpoints

than they already had, thus expanding their overall learning on the

topic much more than if they only debated, defended, or played a role

already in-line with their current worldviews.

Role-play: The instructor assigns roles or characters to learners and then gives

them scenarios to act out in the AOD. Note that

these are great alternative assessment methods and help to really learn

how much learners know about a given topic. An important tactic to

keep in mind is to

survey learners prior to assigning roles and to purposely put each learner into a role that is new or different than the learner's own

personal views or values. For example, make a learner with conservative political views play the

role of a person with liberal political views,

or young person play the role of an elderly resident. This way the

participants are forced to learn about new views and opposite viewpoints

than they already had, thus expanding their overall learning on the

topic much more than if they only debated, defended, or played a role

already in-line with their current worldviews.

Leadership Development.: An

excellent tactic is to make students a leader in the discussions, which

also attends to encouraging students to be in charge of their own

learning. This tactic motivates them to learn at least one topic fully,

and by teaching others they show their grasp of the subject as well as

learn leadership skills.

Leadership Development.: An

excellent tactic is to make students a leader in the discussions, which

also attends to encouraging students to be in charge of their own

learning. This tactic motivates them to learn at least one topic fully,

and by teaching others they show their grasp of the subject as well as

learn leadership skills.

Prud'homme-Généreux, A. (2021). 21 Ways to Structure an Online Discussion. Faculty Focus.

Prud'homme-Généreux, A. (2021). 21 Ways to Structure an Online Discussion. Faculty Focus.

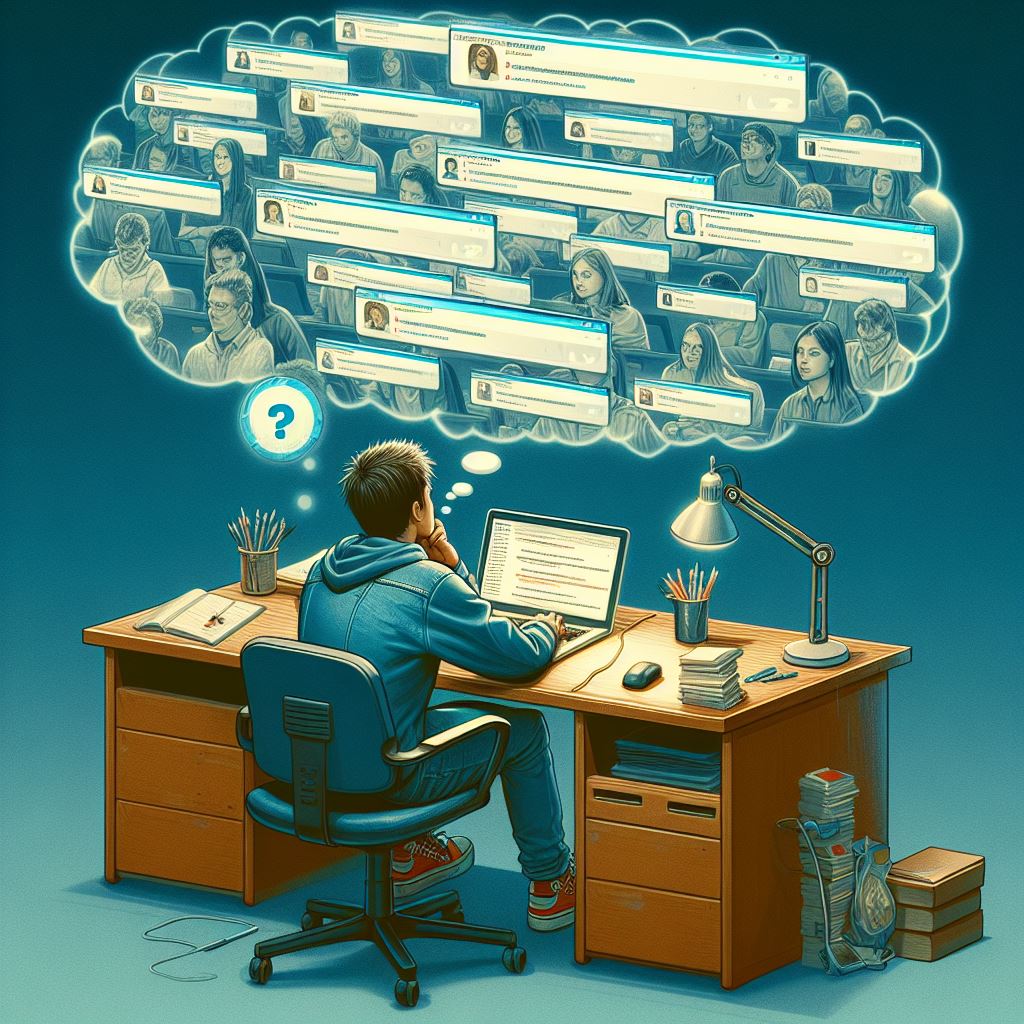

When people

think of AOD, they usually envision a threaded text-based conversations hosted

on their institution’s LMS. That’s certainly one way to go. But there are other

options to consider that vary in the media used. Some may be better at

achieving certain outcomes.

When people

think of AOD, they usually envision a threaded text-based conversations hosted

on their institution’s LMS. That’s certainly one way to go. But there are other

options to consider that vary in the media used. Some may be better at

achieving certain outcomes.  Text-based,

threaded online discussions probably do not need much introduction since most

LMS come with this capability. Depending on the discussion structure, learners

may be required to post only once, or to return to their posts and comment on

the responses they receive. Text-based discussions, because of their linear

structure, can become overwhelming when there are more than about 20

participants. Educators may want to group learners into smaller discussion

groups to make the discussion more manageable.

Text-based,

threaded online discussions probably do not need much introduction since most

LMS come with this capability. Depending on the discussion structure, learners

may be required to post only once, or to return to their posts and comment on

the responses they receive. Text-based discussions, because of their linear

structure, can become overwhelming when there are more than about 20

participants. Educators may want to group learners into smaller discussion

groups to make the discussion more manageable. A

cloud-based, digital whiteboard is in many ways a text-based discussion

(although some platforms also support posting images and videos), but

instead

of a linear experience, participants can access all of the posts at

once, selecting

which one to review in more depth. and the posts can be organized using

frameworks, such as KWL (Know | Want to Know | Learned), or a SWOT

analysis (a table where learners identify the Strengths | Weaknesses |

Opportunities | Threats to a project), or something more specific to

your discipline such as classifying example of cells as belonging to

Prokaryotes or Eukaryotes).

A

cloud-based, digital whiteboard is in many ways a text-based discussion

(although some platforms also support posting images and videos), but

instead

of a linear experience, participants can access all of the posts at

once, selecting

which one to review in more depth. and the posts can be organized using

frameworks, such as KWL (Know | Want to Know | Learned), or a SWOT

analysis (a table where learners identify the Strengths | Weaknesses |

Opportunities | Threats to a project), or something more specific to

your discipline such as classifying example of cells as belonging to

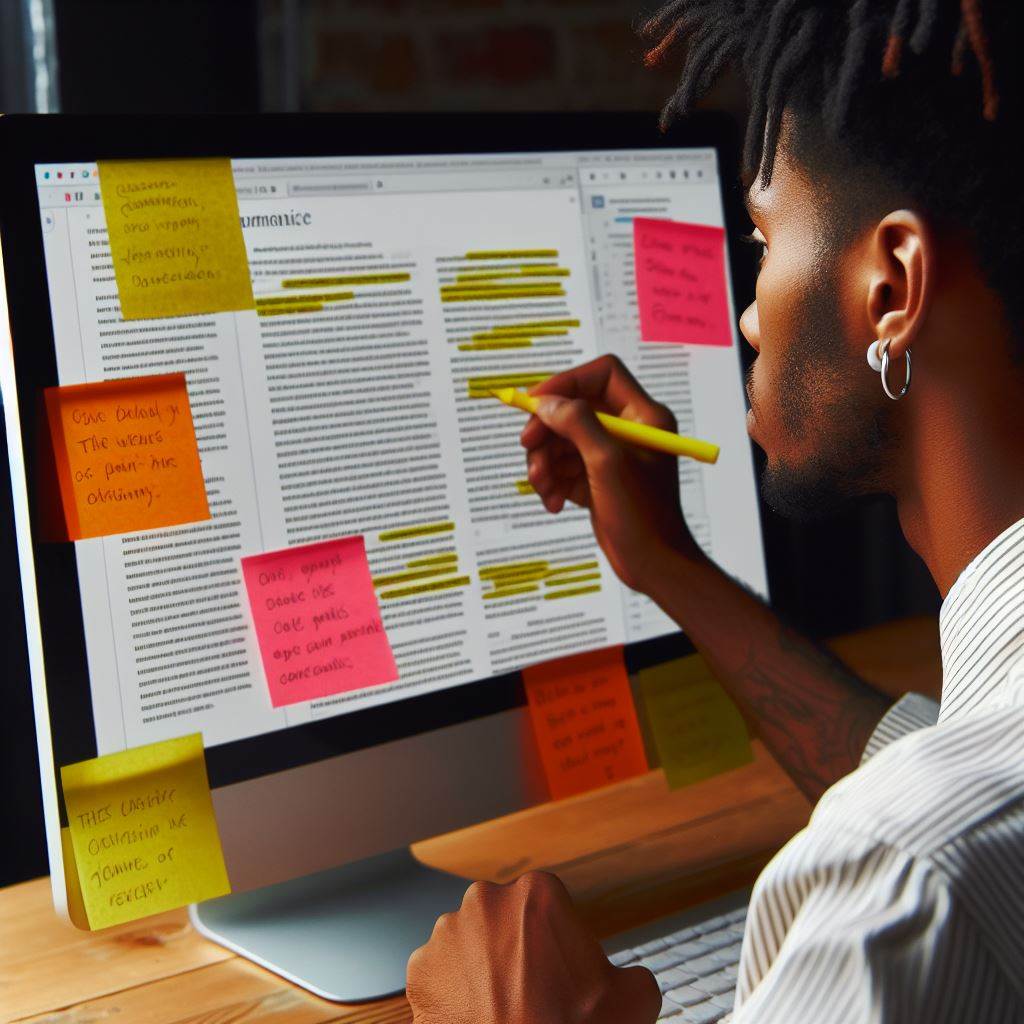

Prokaryotes or Eukaryotes). Annotation

tools allow learners to add comments directly on an existing resource (e.g., a

reading or webpage), see each other’s comments, and respond to it. This permits

the discussion to take place on the resource, rather than

abstracted from it. In a text-based discussion, learners who are discussing a

reading might copy a quote, indicate its page number (its location in the

text), and then add their commentary, whereas with an annotation tool, these

commented are embedded in the text in situ. This permits learners to see

the context in which the comments are made.

Annotation

tools allow learners to add comments directly on an existing resource (e.g., a

reading or webpage), see each other’s comments, and respond to it. This permits

the discussion to take place on the resource, rather than

abstracted from it. In a text-based discussion, learners who are discussing a

reading might copy a quote, indicate its page number (its location in the

text), and then add their commentary, whereas with an annotation tool, these

commented are embedded in the text in situ. This permits learners to see

the context in which the comments are made.

Text

is not the only way to engaged in an online asynchronous discussion.

The discussion can also be done via audio and video recordings. This can

make the discussion more engaging and feel closer to a live

conversation.

Text

is not the only way to engaged in an online asynchronous discussion.

The discussion can also be done via audio and video recordings. This can

make the discussion more engaging and feel closer to a live

conversation. Create a Permanent Discussion Schedule. An instructor

can schedule regular and consistent start and end dates of discussions

to keep learners on track (e.g., first post due every Tuesday at noon, and 2 responses to peers due by Thursday at noon). Setting early due dates on the posts allows learners enough time to reply before the end of the discussions. Making

the discussion schedule a permanent part of the syllabus allows students

to plan their time effectively.

Create a Permanent Discussion Schedule. An instructor

can schedule regular and consistent start and end dates of discussions

to keep learners on track (e.g., first post due every Tuesday at noon, and 2 responses to peers due by Thursday at noon). Setting early due dates on the posts allows learners enough time to reply before the end of the discussions. Making

the discussion schedule a permanent part of the syllabus allows students

to plan their time effectively. In cases where a large majority or most of the students in the course

are English Language Learners, the instructor may need to spend a bit more time

supporting students in the discussions, or offering summaries of new

words and expressions learned via email after the discussions.

In cases where a large majority or most of the students in the course

are English Language Learners, the instructor may need to spend a bit more time

supporting students in the discussions, or offering summaries of new

words and expressions learned via email after the discussions.

Research supports two interesting results that could conflict with

each other in practice: 1) That instructor presence is key to student

satisfaction, and 2) That too much interaction and posting by the instructor

in discussions can lead to reduced posting by the students (Wang and

Liang, 2011).

Research supports two interesting results that could conflict with

each other in practice: 1) That instructor presence is key to student

satisfaction, and 2) That too much interaction and posting by the instructor

in discussions can lead to reduced posting by the students (Wang and

Liang, 2011). Hungry for more? Consider the following resources.

Hungry for more? Consider the following resources. Assigning grades to online discussions is the biggest predictor of their

success. If no grade is assigned, students are less likely to

participate. It’s recommended that participation in online discussions

counts for 10% to 20% of the course grade; research shows that no

additional benefits result when the grade is increased above 20%

(deNoyelles, Zydney, & Chen, 2014).

Assigning grades to online discussions is the biggest predictor of their

success. If no grade is assigned, students are less likely to

participate. It’s recommended that participation in online discussions

counts for 10% to 20% of the course grade; research shows that no

additional benefits result when the grade is increased above 20%

(deNoyelles, Zydney, & Chen, 2014).  Rubrics

Rubrics